End-of-Summer Market Update

Dear Friend,

Speed bump, stop sign, or red light? That’s the question many of us are asking.

Let me explain. After cruising for the past five months, the markets screeched to a halt on September 3, the Dow dropping over 800 points, and the Nasdaq plunging nearly 5%.1 All told, it was one of the worst trading days for stocks since the pandemic-driven panic of March. The volatility continued the next day, albeit at lower levels.

So, what does it mean? Was Thursday’s selloff just a short-term blip—the equivalent of hitting a speed bump? Or was it the beginning of a market correction? If so, how long of a correction? Are we merely coming to a stop sign, or will we hit a red light?

Unfortunately, market signals are never as easy to interpret as road signs. But as we start winding down this bewildering year, investors will be gripping their steering wheels ever more tightly. That’s because they’re all trying to determine whether the markets will end the year on cruise control…or in full reverse.

Whenever you drive to a destination, it’s always good to familiarize yourself with the road beforehand. So, as this crazy summer draws to a close, let’s look at the different scenarios we could experience over the next few months.

As a heads up, we’re going to cover a lot of ground in this message. I believe my most important responsibility is to keep you not only informed about what’s going on in the markets but also prepared for what may come in the future. In this message, I will try to do both. Let’s dive in.

Speed Bumps

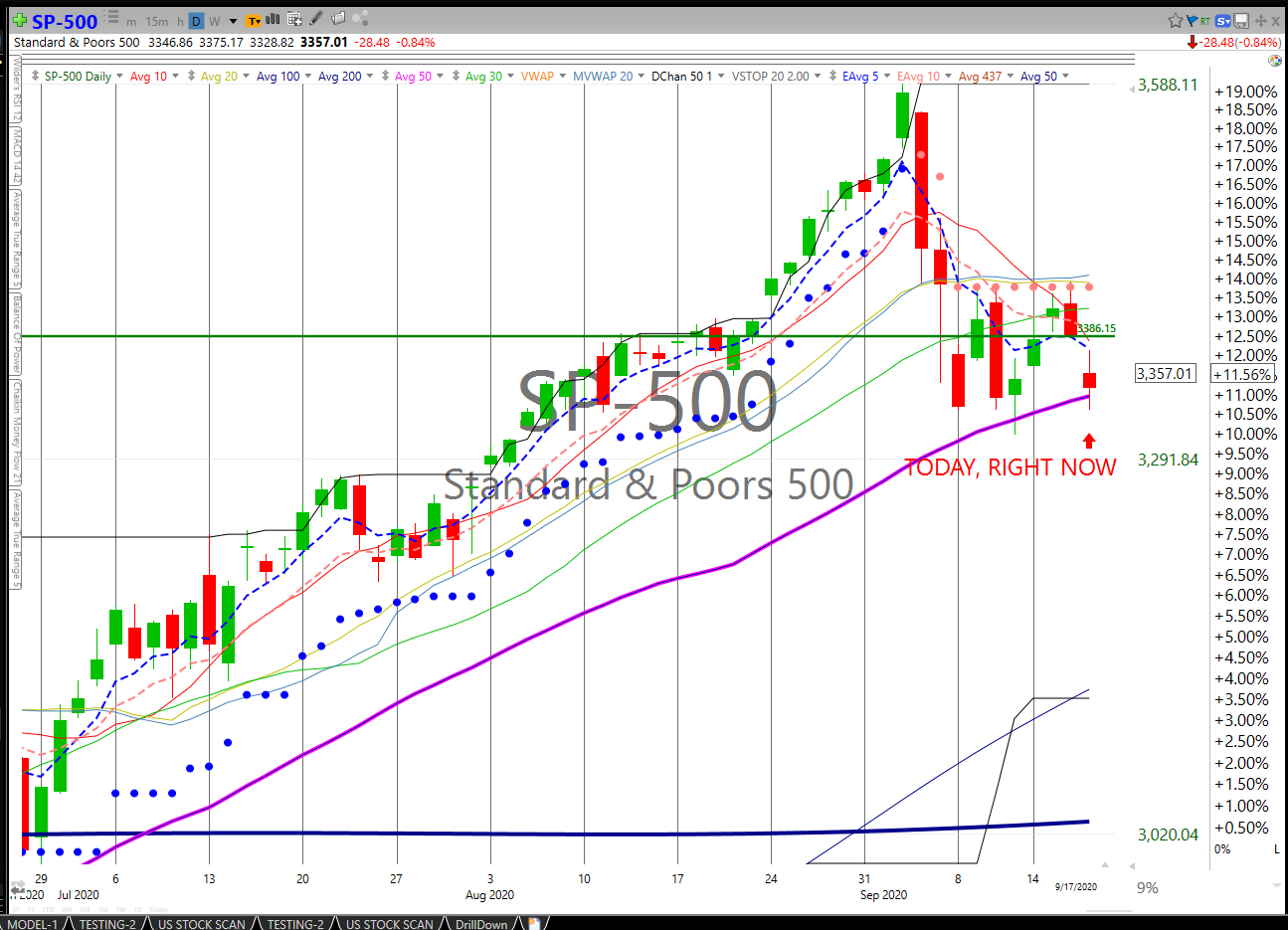

Between April and May, all three major US stock indexes—the Dow, the S&P 500, and the NASDAQ—climbed for five consecutive months. The S&P 500, for example, rose 60% over that period.2

Every so often, though, the markets experience a dramatic one- or two-day selloff. When those selloffs come during the middle of a major rally, like the one we’ve been experiencing, investors wonder whether it’s the beginning of a market correction. (A correction, remember, is when the markets fall at least 10% from their recent highs.)

Market corrections are relatively common. On average, we’ll see one at least once every 1 to 2 years.3 But more often, these selloffs are not the beginning of anything at all. They are simply speed bumps, and while they may seem random, there are usually underlying reasons for them.

For example, let’s take what happened on September 3 and assume it’s only a speed bump. Why did it happen? A closer look at which stocks fell may provide some answers. Specifically, tech stocks, including big names like Apple and Facebook, were the ones that suffered the most—just as those same stocks have largely fueled the markets rally. (More on this in a moment.) There are a few possible reasons for this. One is that many investors may simply have been cashing out of tech stocks to realize their gains. Another reason is that, because prices for tech stocks have risen so high, many traders may feel there’s simply no justification for plowing more money into them. When that happens, traders and short-term investors often move their money into other sectors they feel are undervalued.

In other words, the shudder that went through the markets is like the one you feel when changing gears in an old car. If that’s the case, the selloff was likely just a speed bump. A short pause for investors to take a breath before the markets resume their climb.

Here’s another reason why many selloffs are just speed bumps: The Federal Reserve. After the country went into lockdown, the Federal Reserve did many things to prop up the economy.4 First, it lowered interest rates to historic lows. This was to lower the cost of borrowing on mortgages, auto loans, home equity loans, and others—a key step to keep the economy moving. Second, the Fed launched a massive bond-buying program. This is another way to keep interest rates low. The Fed has also been lending money to securities firms, banks, major employers, and some small businesses using a variety of means.

These are all familiar tactics for anyone who was paying attention during the Great Recession. Then, as now, the Fed’s actions indirectly propelled the stock market. That’s because lower interest rates prompt increased spending, which in turn causes stock prices to rise. And, perhaps more importantly, the Fed’s massive increase in the money supply juices the stock market. After all, that new money wants a home, it wants a return. It looks at bonds and says, No, no return there. And so it rushes into the US stock market.

As long as the Fed keeps its stimulus programs in place, stocks will continue to be one of the most attractive places for people to put their money. And since the economy remains on very shaky ground, it’s unlikely the Fed will pull back any time soon. “Don’t fight the Fed,” investors are often counseled. Thanks in large part to the Federal Reserve, the stock market continues to be the shortest, surest road for investors to travel. That’s why many selloffs are nothing more than speed bumps.

Stop Signs

Of course, sometimes a selloff is more than just a speed bump. Sometimes, it’s like a neon light flashing: STOP SIGN AHEAD.

When this happens, Wall Street-types like to call it a market correction—a decline of 10% or more from a recent high. There are many reasons why corrections occur. One thing many corrections have in common, though, is they come after months of major market growth. When prices rise extremely high, extremely fast, it’s as if the markets have “overheated” and need to cool off.

It wouldn’t be a surprise if that’s what we’re seeing right now. Again, the S&P 500 rose 60% between March 23 (its most recent low) and September 2 (its most recent high).2 In that same period, the tech-heavy NASDAQ rose roughly 75%!5 Those are staggering numbers. One could argue we’re overdue for a correction.

Speaking of tech-heavy, let’s talk about technology stocks for a moment. When the markets plummeted in March, these stocks were one of the few safe havens around—and they’ve also been the best performers since then. That’s no surprise. At a time when most Americans were largely confined to their homes, it was our technology—from our iPhones to Zoom, from Google to Netflix—that kept the economy going. But remember how I said the S&P rose 60%? Peek under the hood and you’ll see those numbers were driven by two sectors: technology stocks and consumer discretionary stocks. (Think Nike, McDonald’s, Home Depot, etc.) Other sectors either performed much lower or are still in the red. So when we say the markets have recovered well, what we’re really saying is that the top sectors have performed enough to make up for those still struggling.

It’s one of the many reasons the stock market simply isn’t a reliable barometer for the overall economy.

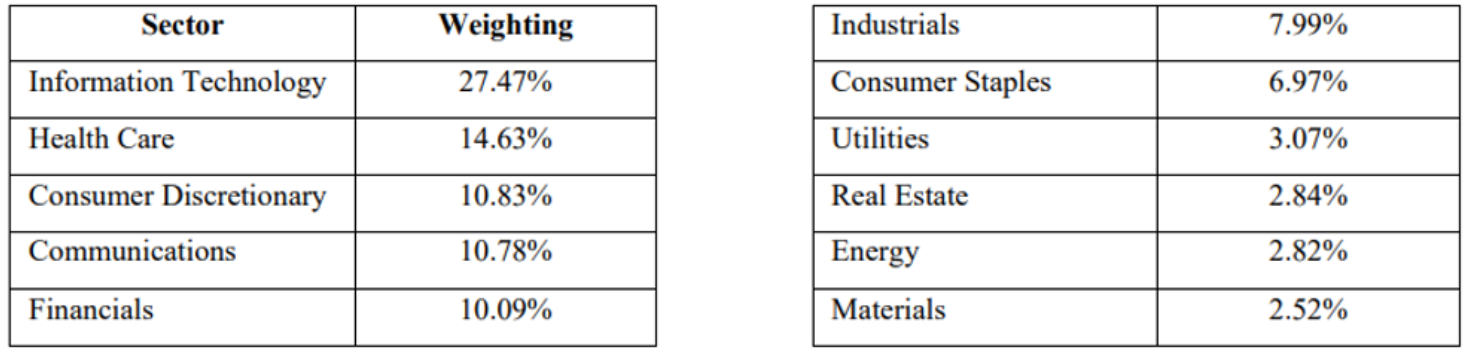

What does this have to do with a market correction? A lot, actually. It’s all thanks to these two terms: capitalization and weighting. Remember, the S&P 500 is an index, not the actual stock market itself. It’s essentially a collection of the five hundred largest companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges, which is where stocks are traded. More specifically, the S&P is a capitalization-weighted index. Without getting too technical, that means the largest companies make up the largest percentage of the index. For example, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, and Google—just five companies—make up 20% of the index!6

Look at that list of companies again. Notice anything about it? Yep, you guessed it: four of them are tech companies. In fact, if we break down the S&P 500 by sector, you’d notice that technology dominates the S&P 500. Actually, let’s do that right now.7